Alfa Romeo: Masculinity in Metal, From Menace to Seduction

I spent an afternoon wandering the Alfa Romeo Museum outside Milan, expecting a pleasant stroll through automotive history. Instead, it felt like walking through the emotional evolution of Italian masculinity: from raw, mechanical violence to refined seduction, and then, at times, back to insecurity and confusion. Few car companies wear their eras so honestly on their sheet metal.

1930s — Pure Mechanical Menace

The pre-war Alfas are not “beautiful” in the traditional sense. They are imposing. Long hoods stretched over monstrous straight-eights, radiators like armored jaws, wheels and suspensions fully exposed. These were not cars built for comfort or elegance, they were weapons. Many of their drivers died piloting them. And yet, this brutality forged Alfa’s identity. It launched the careers of racing legends, including a young Enzo Ferrari, and established a template: Alfa would always be emotional first, rational second.

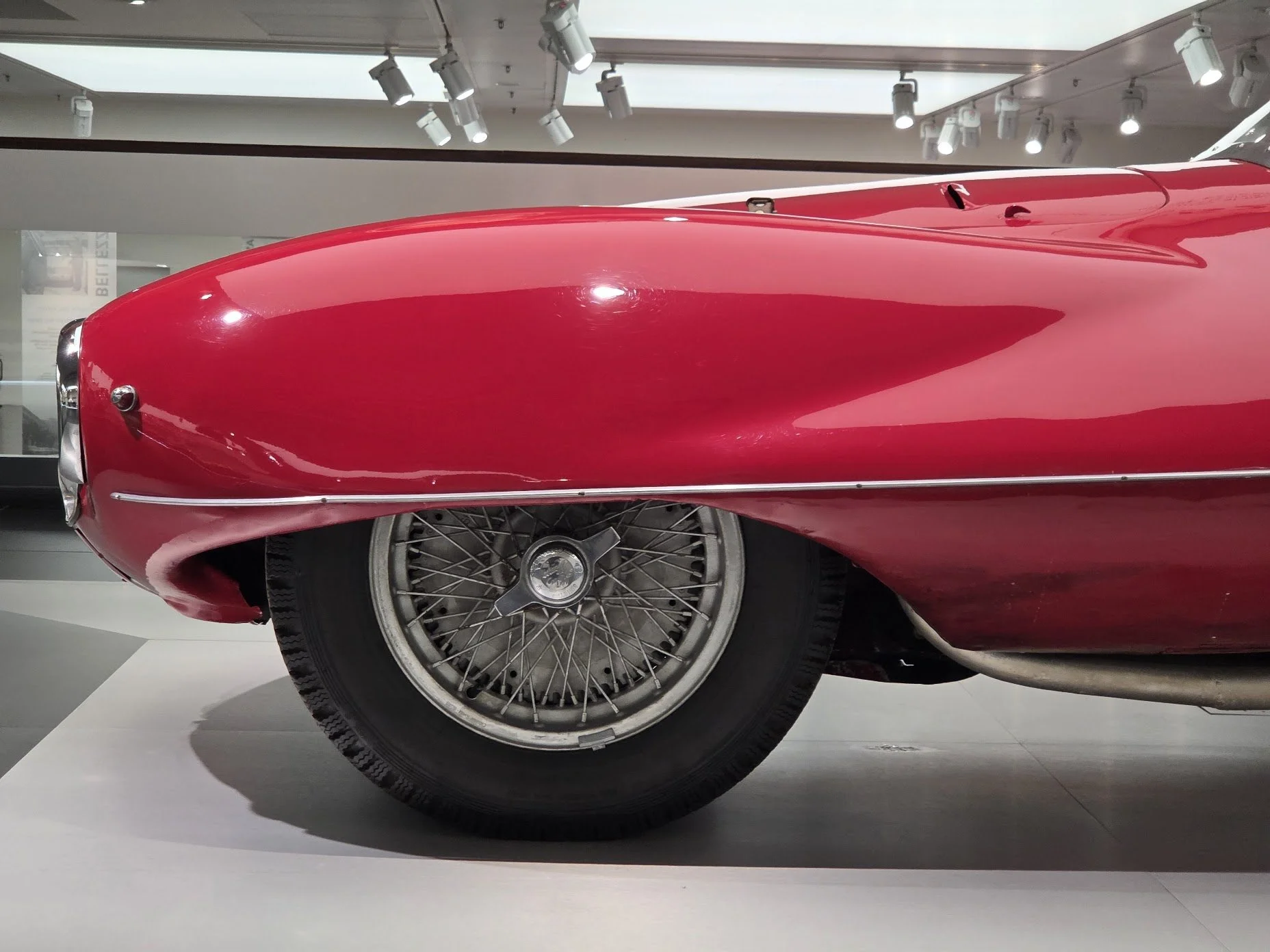

1950s — The Birth of Beauty

Then the war ended, and Alfa discovered softness. The 1950s cars are pure Dolce Vita: flowing fenders, playful fins, joyful proportions. They’re compact, friendly, even a bit flirtatious. There is no aggression in them, just optimism. If the 1930s were defined by brute force, the 1950s were defined by grace. Alfa learned that masculinity could be beautiful.

1960s — Tension and Discipline

The 1960s introduced structure without losing sensuality. Lines sharpened. Stances widened. Cars got slightly larger and more confident, without tipping into arrogance. The Giulia Sprint GTA, my personal favorite, is the perfect synthesis: muscular yet elegant, disciplined yet playful. Masculinity here is not about domination. It’s about balance.

1970s — Experimentation and Ego

Then Alfa hit puberty. The 1970s cars are delightfully weird. Wedge silhouettes, geometric creases, spaceship-like concept cars such as the 33 Stradale derivatives. It's Alfa asking, “What if beauty was also wild?” Some of it landed. Some didn’t. But the confidence to experiment was admirable, and uniquely Italian.

1980s — The Sterile Years

The 1980s are a sobering section of the museum. Boxy sedans stripped of romance. Cost-cutting visible in every flat panel. There are hints of style, a curve in a taillight, a flourish in a grille, like traces of former glory. But overall, it’s masculinity constrained by economics. A man wearing a suit he couldn’t afford to tailor.

1990s — Recovering Form, But Not Soul

The 1990s restored some curvature and form, but rarely produced a truly beautiful object. These cars were correct rather than seductive. Alfa was trying to re-learn itself but hadn’t yet rediscovered its purpose.

2000s — Swagger Returns

The 2000s brought a comeback. Alfa nailed the front end again, the triangular scudetto grille became sculptural, aggressive, proud. Executive saloons wore their emotion without apology. And then came the 8C Competizione: a modern sculpture. Perhaps the last car built with no compromise between beauty and performance.

2010s — Passion Meets Fragility

Under Sergio Marchionne, Alfa made one more charge at greatness. The Giulia Quadrifoglio is a genuinely brilliant sedan, dynamically as good as the Germans, and far more soulful. But Alfa’s eternal flaw resurfaced: passion without infrastructure. Reliability issues betrayed customers on the higher end Quadrifoglio models. Italians built the body of a god but didn’t finish the job.

What Modern Automakers Should Learn

Alfa teaches a brutal truth: Without emotion, nothing matters; yet emotion alone is not enough.

Electric and luxury auto manufacturers today obsess over efficiency, sustainability, range anxiety. All valid. But where is desire? Where is the curve that makes you stare back when you park it?

If Alfa has a future, and I desperately hope it does, it lies in:

Semi-affordable cars with heroic dynamics (what Jaguar was at their best).

A single, unforgettable halo model: perhaps a clean reinterpretation of the Guilia TZ2.

Absolute reliability, not as an engineering achievement, but as respect for the passion of the buyer.

Because the Alfa spirit, at its best, is Milanese: elegant, confident, occasionally reckless, but always committed to beauty.

Walking out of the museum, surrounded by Rosso Alfa paint and names like Bertone, Pininfarina, Zagato, Giugiaro, I realized something:

To build something meaningful, you must risk excess.

Better to be unreliable and unforgettable than perfect and anonymous.

And that, in steel and paint, is the Italian way.